Every war begins in blind folly and ends in unimagined suffering. This is true of all wars but especially of the First World War. Its catalysts were so trivial and its consequences so apocalyptic that they belong in a Swiftian satire of human stupidity: the shooting of a bewhiskered potentate, followed by a botched game of diplomatic chicken, armies mobilized across Europe and cheered on by delirious publics, a whole generation sent to die by the millions in industrial warfare-all for a few miles of mud and barbed wire. Between the assassination in Sarajevo, the mass slaughter in the trenches, and the stagnant front lines lie disproportions so immense that cause and effect lose all relation. The conflict is a sustained demonstration of war's essential inanity. "Every war is ironic because every war is worse than expected," the critic Paul Fussell wrote in The Great War and Modern Memory. By this standard, World War I was the most ironic war in history.

What did the soldiers of the Great War think they were going off to defend? King, kaiser, czar, empire, democracy, European civilization, national honorthe reasons, in hindsight, make no sense. By 1917, the meaninglessness of the sacrifice had become clear enough to the combatants, if not to civilians back home: French and Russian troops mutinied, tens of thousands of soldiers on both sides deserted, the British poet and captain Siegfried Sassoon made a public anti-war declaration, and English war poetry turned brutal and bitter. Yet most soldiers, including Sassoon, fought on, under intolerable conditions-rain-soaked and hungry; facing machine-gun fire, shelling, and chlorine gas; surrounded by the half-buried corpses of their comrades and enemies until the last minute of the last hour before the armistice on November 11, 1918, when, to quote John Kerry, an unknown soldier became "the last man to die for a mistake."

この記事は The Atlantic の March 2025 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,000 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です ? サインイン

この記事は The Atlantic の March 2025 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,000 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です? サインイン

When Robert Frost Was Bad

Before he became America's most famous poet, he wrote some real howlers.

ALL THE KING'S CENSORS

When bureaucrats ruled over British theater

CAPITULATION IS CONTAGIOUS

By killing a cartoon that lampooned its owner, The Washington Post set a dangerous precedent.

The Experimentalist

Ali Smith's novels scramble plotlines, upend characters, and flout chronologywhile telling propulsively readable stories.

The Moron Factory

April 20: Sometimes feel life stinks, everything bad/getting worse, everyone doomed.

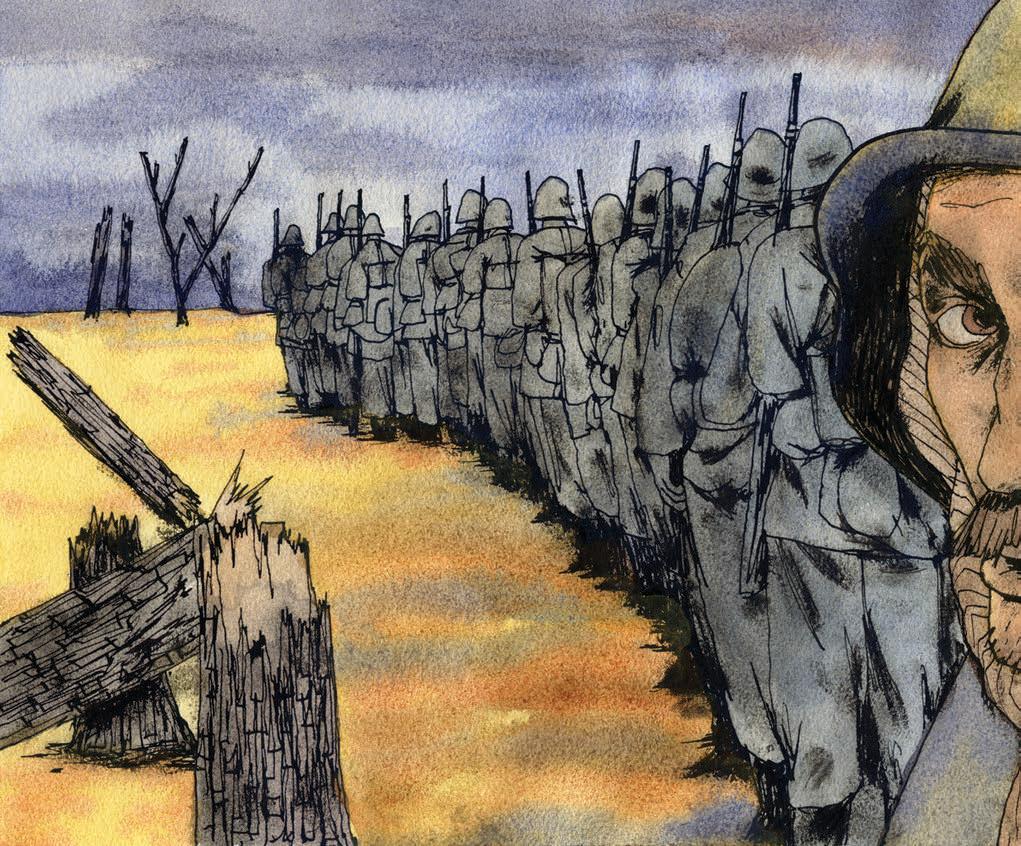

The Warrior's Anti-War Novel

In All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque invented modern war writing.

"I Am Still Mad to Write"

How a tragic accident helped Hanif Kureishi find his rebellious voice again

BEHOLD MY SUIT!

A LIFETIME OF FASHION MISERY COMES TO AN END.

WHY THE COVID DENIERS WON

Lessons from the pandemic and its aftermath

CAN EUROPE STOP ELON MUSK?

He and other tech oligarchs are making it impossible to conduct free and fair elections anywhere.